Religion

As the official religion of the Sassanid Empire, Zoroastrianism touched all aspects of Sasanian life, from literature and the arts to career-making and imperial policy. Each inscription comments on different facets of Sasanian religion. As discussed in "Kingship," Shapur's inscription reckons with divine authority and the king's religious obligations. Narseh invokes the Zoroastrian binary of Ohrmazd and Ahriman in comparing himself with Wahnam. Kerdir's inscription deals most directly with worship and religion as an institution. As such, the majority of evidence in this section will come from Kerdir's inscription.

Power Politics

Religion played heavily into the Sasanian conception of power. Those viewed as most dutiful to Ohrmazd (e.g., Kerdir) were granted a greater share of power within the empire. Kerdir was able to attain a high position because of his extensive religious works: "for that service which I have done towards the gods. . . [Shapur] made me absolute and authoritative in (the matter of) the rites of the gods" (2). Of his final promotion by Bahram II, he writes, "for love of Ohrmezd and the gods and [for] his own soul he made for me in the empire a higher position and honour" (9). These lines show that there existed a sort of religious meritocracy in which individuals could accrue honor and prestige for themselves by augmenting that of the gods.

On the other hand, enemies and imposters were held to be consorts of Ahriman. In his inscription, Narseh explains his victory through the binary of truth and falsehood represented by Ohrmazd and Ahriman. He refers to himself as a "Mazdaean Majesty" and to Wahnam as one who acted "[(with) the help?] of Ahrimen and the devils" (2). Upon his surrender, Wahnam is quoted as saying, "For [that?] sorcery which I have performed there is henceforth no [other?] salvation [for me?] than(?) by the gods and [the King] of Kings" (24). In this way, Narseh frames his attack on Wahnam and Bahram as a righteous crusade against evil. Accusing one's enemies of "sorcery" and assisting "the devils" was clearly a powerful political tool.

On the other hand, enemies and imposters were held to be consorts of Ahriman. In his inscription, Narseh explains his victory through the binary of truth and falsehood represented by Ohrmazd and Ahriman. He refers to himself as a "Mazdaean Majesty" and to Wahnam as one who acted "[(with) the help?] of Ahrimen and the devils" (2). Upon his surrender, Wahnam is quoted as saying, "For [that?] sorcery which I have performed there is henceforth no [other?] salvation [for me?] than(?) by the gods and [the King] of Kings" (24). In this way, Narseh frames his attack on Wahnam and Bahram as a righteous crusade against evil. Accusing one's enemies of "sorcery" and assisting "the devils" was clearly a powerful political tool.

Proselytism

Kerdir dedicates most of his inscription to praising Ohrmazd and listing his accomplishments under each king. However, he also makes passing references to state-sponsored proselytism and acts of severe religious intolerance. For example, line 11 proclaims that "Jews and Buddhists and Hindus and Nazarenes and Christians and Baptists and Manichaeans were smitten in the empire, and idols were destroyed and the abodes of the demons disrupted and made into thrones and seats of the gods" (11). What this suggests is that Zoroastrianism grew more prevalent in the empire on account of the wholesale suppression of other religions. Here, Kerdir admits to engaging in iconoclasm and violently persecuting members of dissenting faiths. In line 16, he proudly testifies to a campaign of forced conversion: "the heretics and the destructive men, who in the Magian land did not adhere to the doctrine regarding the Mazdayasnian religion and the rites of the gods--them I punished, and I tormented them until I made them better." While Kerdir and the early kings surely did convert some practitioners organically, their intolerant practices left many of their subjects with no choice but to adopt the state religion.

Revelation

The KNMr and KSM versions of Kerdir's inscription are unique in that they include a revelation of the Zoroastrian afterlife. Firstly, we ought to unpack the revelation's eschatological significance. Secondly, we should consider why Kerdir chose to include the revelation in his inscription and what it contributes to our understanding of the Sasanian religious project.

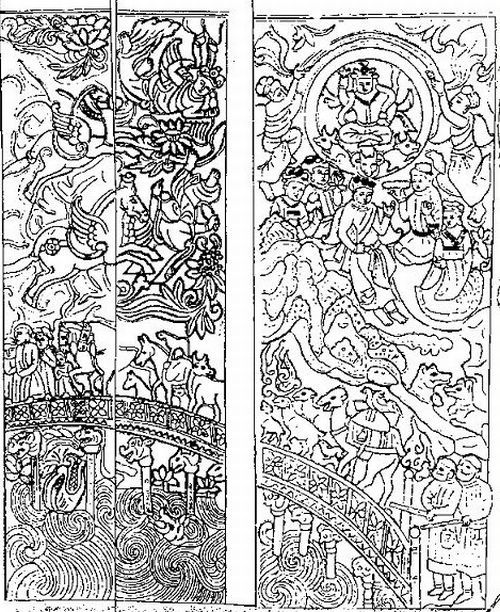

After praying to the gods to "show [him] the nature of Heaven and Hell" (22), Kerdir puts his helpers in a death-like trance and asks them to report what they see. Kerdir's helpers observe two individuals: "one appearing like Kerdir himself" and a noble woman (26). They also observe three princes: one "princely horseman," one "seated on a golden throne" with a set of scales, and another enthroned, "more noble than those seen before" (25, 27, 28). The helpers tremble at the sight of "a [very wide ? pit] having no bottom, and being full of snakes and [scorpions]," but they notice "a blade. . . set over that pit like a bridge" (28-30). With some background knowledge, these images can be fully explained. In Zoroastrian eschatology, the gods Sraosha, Rashnu, and Mithra (the three princes) weigh the deeds of the dead (hence, the scales). If they are judged to be righteous, their den, or soul, appears to them as a beautiful woman, and the Chinvat Bridge (the blade) widens to allow them into heaven. If they are judged to be wicked, their den appears as a hag, the bridge narrows, and they tumble down into hell (the snake-filled pit). In the revelation, Kerdir's den appears to him as a noble, beautiful woman, and the Bridge widens when he and the woman approach. In short, this vision is meant to confirm Zoroaster's teachings and to foretell Kerdir's acceptance into heaven.

In the context of the inscription at large, Kerdir's revelation serves to assure readers of the truth and power of the Zoroastrian faith. After sharing his revelation, Kerdir prays, "whosoever may see this memorial and read it out, let him be more liberal and true to the gods. . . let him also be more confident in this worship and the rites and the Mazdayasnian religion" (37). To that end, the revelation is also polemical in that it rejects other religions' claims to truth. Furthermore, in boldly asserting that he already has a place in heaven, Kerdir props himself up as a paragon of virtue and grasps at eternal life. Though the spiritual world is occluded from us, the persistence of Kerdir's legacy to this day is indeed a sort of immortality.

After praying to the gods to "show [him] the nature of Heaven and Hell" (22), Kerdir puts his helpers in a death-like trance and asks them to report what they see. Kerdir's helpers observe two individuals: "one appearing like Kerdir himself" and a noble woman (26). They also observe three princes: one "princely horseman," one "seated on a golden throne" with a set of scales, and another enthroned, "more noble than those seen before" (25, 27, 28). The helpers tremble at the sight of "a [very wide ? pit] having no bottom, and being full of snakes and [scorpions]," but they notice "a blade. . . set over that pit like a bridge" (28-30). With some background knowledge, these images can be fully explained. In Zoroastrian eschatology, the gods Sraosha, Rashnu, and Mithra (the three princes) weigh the deeds of the dead (hence, the scales). If they are judged to be righteous, their den, or soul, appears to them as a beautiful woman, and the Chinvat Bridge (the blade) widens to allow them into heaven. If they are judged to be wicked, their den appears as a hag, the bridge narrows, and they tumble down into hell (the snake-filled pit). In the revelation, Kerdir's den appears to him as a noble, beautiful woman, and the Bridge widens when he and the woman approach. In short, this vision is meant to confirm Zoroaster's teachings and to foretell Kerdir's acceptance into heaven.

In the context of the inscription at large, Kerdir's revelation serves to assure readers of the truth and power of the Zoroastrian faith. After sharing his revelation, Kerdir prays, "whosoever may see this memorial and read it out, let him be more liberal and true to the gods. . . let him also be more confident in this worship and the rites and the Mazdayasnian religion" (37). To that end, the revelation is also polemical in that it rejects other religions' claims to truth. Furthermore, in boldly asserting that he already has a place in heaven, Kerdir props himself up as a paragon of virtue and grasps at eternal life. Though the spiritual world is occluded from us, the persistence of Kerdir's legacy to this day is indeed a sort of immortality.

Bibliography

"ČINWAD PUHL" (Chinvat Bridge), Encyclopædia Iranica, V/6, pp. 594-595, available online at https://iranicaonline.org/articles/cinwad-puhl-av