Form

Visual and Literary

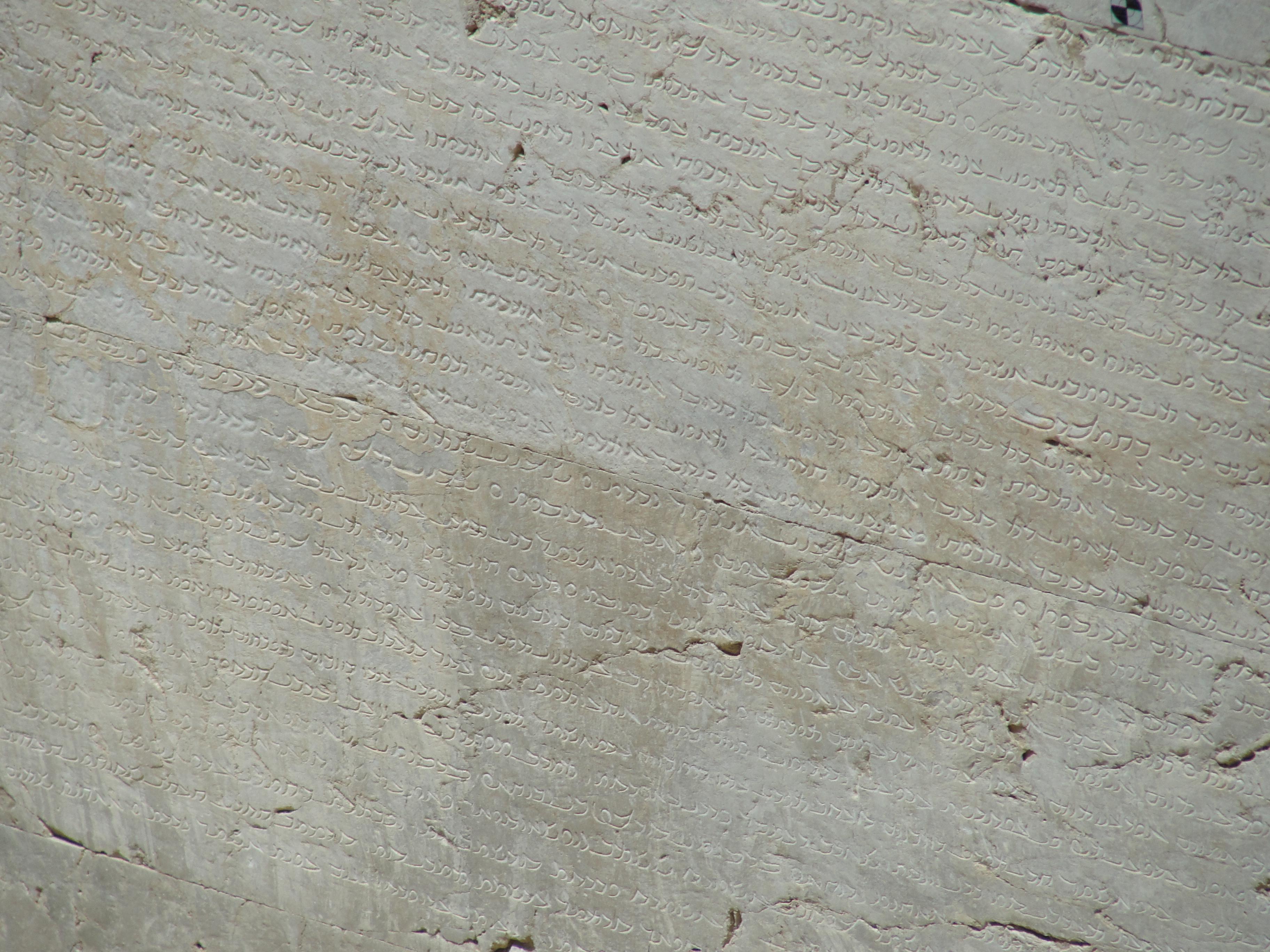

In addition to geography, the visual presentation and literary form of Shapur, Narseh's, and Kerdir's inscriptions make for interesting points of comparison.

All three inscriptions were executed on prepared sections of large, upright rock faces (some natural, some man-made). This might seem trivial, but given the variety in form of other Near Eastern inscriptions, this is a salient feature. For instance, Cyrus the Great's inscription survives on the surface of a football-sized cylinder, the Safaitic inscriptions were made on plain stones scattered across the Jordanian desert, and the Epic of Gilgamesh was inscribed on clay tablets. In terms of visual form, the royal Sasanian inscriptions share similarities with the Behistun (Bisotun) inscription of Darius I.

All three inscriptions were executed on prepared sections of large, upright rock faces (some natural, some man-made). This might seem trivial, but given the variety in form of other Near Eastern inscriptions, this is a salient feature. For instance, Cyrus the Great's inscription survives on the surface of a football-sized cylinder, the Safaitic inscriptions were made on plain stones scattered across the Jordanian desert, and the Epic of Gilgamesh was inscribed on clay tablets. In terms of visual form, the royal Sasanian inscriptions share similarities with the Behistun (Bisotun) inscription of Darius I.

Darius had his inscription carved directly into the face of Mount Behistun. The text is organized into distinct blocks and accompanies a relief of Darius subduing conspirators and pretenders to the throne. Kerdir's inscription at Naqsh-e Rostam bears the most striking similarity to the Behistun inscription in that the text is contained within a rough block and complements a triumphal relief (compare the photo at left with the one above). In addition, Darius's inscription is multilingual (Elamite, Old Persian, and Babylonian) much like Shapur's (Middle Persian, Parthian, and Greek) and Narseh's (Middle Persian and Parthian).

However, Shapur and Narseh's inscriptions appear on man-made towers rather than natural surfaces. While the medium (upright stone) remains the same, their form adds a layer of depth. Architecture demonstrates command of science, art, and to a degree, the natural world; moreover, erecting a tower is an accomplishment in and of itself. Thus, the high architectural value of the Ka'ba-ye Zartosht and Paikuli Tower enhances Shapur and Narseh's claims to wisdom and authority.

However, Shapur and Narseh's inscriptions appear on man-made towers rather than natural surfaces. While the medium (upright stone) remains the same, their form adds a layer of depth. Architecture demonstrates command of science, art, and to a degree, the natural world; moreover, erecting a tower is an accomplishment in and of itself. Thus, the high architectural value of the Ka'ba-ye Zartosht and Paikuli Tower enhances Shapur and Narseh's claims to wisdom and authority.

In terms of literary form, all three royal Sasanian inscriptions are documentary and celebratory texts in that they praise and preserve each individual's accomplishments. Along with works such as the Cyrus and Antiochus Cylinders, the Behistun inscription, and Ashurnasipal II's temple walls, they fall under a genre which might be dubbed 'commemorative literature.' While Shapur and Kerdir's inscriptions commemorate their entire careers, Narseh's is slightly different in that it focuses mainly on his ascension and confirmation. However, Paikuli Tower clearly stands as a monument to Narseh's entire reign, and much like Narseh, Darius dedicates much of his inscription to narrating how he consolidated power.

One interesting feature of Narseh and Shapur's inscriptions is that they memorialize people as well as deeds. Shapur lists his entire court and those of his predecessors, and Narseh names all the aristocrats and dignitaries who supported him. Thus, these inscriptions are just as much historical and anthropological texts as they are commemorative and literary. Likewise, Kerdir's inscription commits names and deeds to history, but it also overlaps with religious and revelatory literature due to its prayer-like language and description of the afterlife.

One interesting feature of Narseh and Shapur's inscriptions is that they memorialize people as well as deeds. Shapur lists his entire court and those of his predecessors, and Narseh names all the aristocrats and dignitaries who supported him. Thus, these inscriptions are just as much historical and anthropological texts as they are commemorative and literary. Likewise, Kerdir's inscription commits names and deeds to history, but it also overlaps with religious and revelatory literature due to its prayer-like language and description of the afterlife.